Civil Rights and Financing Elections

“Money On My Mind” is a monthly column by Jay Mandle. The views expressed here are those of the author, (not necessarily those of Democracy Matters or Common Cause), and are meant to stimulate discussion.

By Jay Mandle

In this “Money on My Mind” I will argue that our failure to treat the electoral system as a public good gets in the way of achieving racial justice. Campaign finance reform is a civil rights issue. It is all but impossible to envision progress in achieving racial equality unless and until the role of private wealth in the electoral system is eliminated.

All societies require their governments to provide certain services to its citizens. These are “public goods.” Economics textbooks point to national security, policing, and the highway system as examples of such services. But there are no hard and fast rules concerning what public goods are or should be. Whether profit-seeking firms or the public sector should supply a service is a political decision.

For example, we choose to provide policing as a public service. We do so because we conclude that police services would not be made available fairly and adequately if they were marketed privately. If policing were not publicly supplied, the rich would be well protected, but those unable to pay the market price would go un-policed or at best under-policed. Rather than risk the chaos that would result, we treat policing as a public good that should be available to all, whether or not they can pay for it.

In contrast, we have chosen not to consider elections as public goods. Instead, candidates run for office depending upon private donors to pay for their election campaigns. The result is clear. Politicians have to be more responsive to their contributors than to non-contributors. Their careers are dependent upon victory at the polls, and the campaigns necessary to achieve that goal are expensive. Because the electoral process is financed privately the outcome of the political process is tilted to the interests of those who buy the service.

With this the case, our electoral system places people of color at a severe and self-reinforcing disadvantage. Because African Americans, Latinx and Native Americans disproportionately are poor, they contribute significantly less to political campaigns than White people. Because this is so, politicians are less attentive to the interests of racial minorities. This neglect, in turn, reinforces minority poverty and marginality.

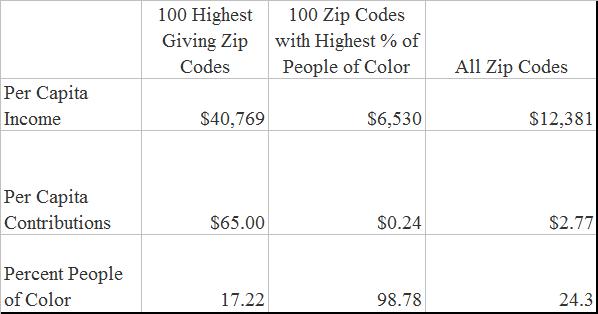

Data collected by Public Campaign suggest the extent to which our campaign finance system excludes racial minorities from political influence. Public Campaign collected information about the racial composition of zip code districts in the United States and then matched it to data showing private political contribution of $200 or more in those districts. This allows us to compare the racial composition of the largest contributing zip code areas with the contributions made in zip codes dominated by racial minorities, and both of these can compared with the pattern of contributions for the United States as a whole. A summary of this data is provided in the table below.

Table 1

Per Capita Income, Per Capita Political Contributions and Percent People of Color, by Zip Code

The pattern is truly amazing. The table reveals that the zip code districts in which campaign contributions are highest are immensely more wealthy, and more white, than is the country as a whole. The difference between these wealthy zip code areas and those dominated by people of color makes it seem almost as if we are comparing two countries at different levels of economic development.

But from the perspective of the electoral system, the statistic of greatest significance is the per capita contributions made by zip code residents. With this statistic we are looking at the motive force of a privately funded system and it is here that we see why the interests of racial minorities receive short shrift politically. For there simply is no way that people of color can be treated fairly in a political system in which politicians receive about $0.24 per person from them, when others, wealthy and typically white, on average contribute $65.00 per person.

The vicious cycle of poverty and disempowerment that these data suggest point to one conclusion: reducing inequalities in the funding of elections is required in order to narrow racial inequalities in society. An electoral system paid for by the wealthy cannot be one in which relatively low income racial minorities participate on a basis of equality. The goal of racial justice cannot be separated from the way we pay for the electoral campaigns of politicians.

What all of this means is that the time has arrived for us to consider the electoral system as a public good. Paying for electoral campaigns on a basis of equality, with tax money, would be an important step in the direction of overcoming he historical legacy of racism in this country. Campaign finance reform is indeed a civil rights issue.